Author: Yi Xian

If the pressure on social security expenditure is gradually increasing facing an aging society for China, the tension on pension investing funds will be built up even worse in Japan, which has already entered an aging society in advance.

So how does Japan government solve this problem?

For Government Pension Investment Fund, what mistakes did government make? What success has it achieved?

The savior of Japan: Government Pension Investment Fund

The Japanese Government Pension Fund (GPIF) is known as the world’s largest pension fund. It is presented in the form of annuity. Japan’s pension system is called the “annuity system” and pensions are called “annuities”.

In Japan, there are two types of “annuities”, one is the National Annuity, also known as the basic annuity. All citizens in the prescribed age group can participate and enjoy the welfare of this annuity. The other kind is the Welfare Pension and the Mutual Pension, which are related to income. Company employees and civil servants can be counted as valid to enjoy this welfare according to their identities. Japan’s pension model pursues the principle of “national centralism”, so that the government is in charge of the pension funds. The Welfare Pension and the National Pension are managed by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, and the Mutual Annuity by each Mutual Aid Associations. The 2/3 income of the National Pension comes from the premiums collected and 1/3 comes from the government’s financial subsidies.

As for the investment in pension funds in the past few years, the main investment categories of Japanese pension insurance are: venture capital, High Beta stocks, junk bonds, and even US infrastructure projects was counted in, according to public reports. Reported by Nikkei News on February 10, 2018, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Trump agreed on the framework of GPIF’s investment in US infrastructure and the draft proposal covered the following: Japan’s investment in United States infrastructure includes joint robotics, artificial intelligence research, and strategies against cyber attacks. The investment is implemented by GPIF purchasing bonds issued by US companies to finance infrastructure projects.

It is reported that 5% of GPIF asset can be used to invest in overseas infrastructure constructions, which is about 130 trillion Yen ($1.14 trillion). At present, the investment in this category of assets is only tens of billions of Yen.

In general, in addition to some diplomatic needs, Japan’s pensions have a major impact on the construction and economic development of the country – it can be said that, in Japan, pension is the cerebral of entire fund system, operating via the capital division of the Ministry of Finance, which categorizes different types of funds into the areas where funds are needed. Simply put, it is a coordinator for planning and scheming.

This is related to the generation of Japanese pensions.

After the World War II, Japan was in ruins; the weak private capital could barely meet the requirement of those major infrastructures. As a result, Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida put pension insurance fund into Japan’s infrastructure construction, which led to a very significant result. Unlike Europe and the United States, Japan government has devoted its willpower into the financial system through public financial institutions. Therefore, Japanese pensions have the reputation of “second finance”.

Why do we call it that?

Because, in general, pension funds are large-scale, which are expected to achieve long-term returns, and often required capital expenditures decades later. Such funds are almost tailored to the infrastructure. For example, in 1964, when Japan built the Shinkansen, the total investment was up to 380 billion yen. Where did the money come from? Japan decided to continually invest in construction. It can be said that the post-war economic prosperity of Japan was closely associated to trillions of pension funds. Later, the chief designer of China’s Reform and Opening up , Deng Xiaoping, took the Shinkansen and instructed everyone: “We got to learn all useful technical and managerial experience!”

In the 1970s, the overall industrial technology in Japan was still relatively vulnerable. In order to boost industry evolution, Japan invested a large amount of long-term funds in the heavy industry. The Fund became shareholders of companies including Mitsubishi, high-speed internal combustion engine, Kawasaki, Kyoto, Toyota, Nissan, Isuzu and so on. To be more specific, Japan’s initial capital accumulation is not essentially predatory like the European and American style, but a virtuous circle of endogenous funds. This is significantly different from Europe and the United States style.

Reformation of pension funds: Marketization of the turn in 80s

In the 1980s, as the world’s economy changed, for example, market-oriented operations had been implemented to pensions in Europe and the United States, of which the pensions were invested as capital where global demographic dividends were high to alleviate the pension crisis. In the early 1980s, they completed positioning the stock market and enjoyed the dividend from economic development in the future. Yet at this time, Japan was still trapped in the pretty illusions of large-scale investment in the past.

Nevertheless, Japan’s pension hasn’t stayed the same.

For example, since 1986, the Japanese government has allowed some of the annuities to be put into the stock market, but the first attempt ended failing – though the timing to enter the market in 1986 was not too late, Japanese pensions were less open; gradually the large-scale acquisition of leverage between 1987 and 1990, estimated to be between 22,000 and 25,000 caught up with the bubble in 1990s. After the bubble burst in 1990, Japanese pensions still stuck with the concept of long-term investment. Japan didn’t begin to block on a large scale until after the cost line finally crashed down. As a result, the selling pressure was like a significant rush.

Subsequently, the investment concept of Japanese pension changed to the value of “fall more and big more” and “fall less and small less”, and constantly reduced costs. As a result, the Nikkei index stayed at 10,000 points for a few years unexpectedly.

Pensions fall into the immensely desperate situation.

The pension fund was so depleted, what about the pension itself?

This loss directly forced the reform of marketization of Japanese pensions. In 2001, Japan put the pension market into operation, transferred from the Ministry of the Finance to the unified management of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, and established funds for the operation of pension funds. After the reform, Japan’s pensions seem to be revived, continuously making profit from 2003 to 2006, with profits more than 60%. But once the financial crisis came, it was returned to its old shape, and the income of the year decreased to -27.97%!

However, Japanese pensions still insisted on the proportion of the stock market.

Increasing the proportion of public pensions invested in the stock market for sure was an important part of Abenomics.

On October 31, 2014, GPIF announced that it would double its asset allocation to domestic and foreign stock markets. Increase the proportion of assets allocated to Japanese and foreign stock markets from 12% to 25%, while reducing the proportion of domestic bond allocation from 60% to 35%, and increase the allocation ratio of overseas bonds from 11% to 15%; in the end, 50% of bond investment and 50% of stock market investment will be realized.

At that time, when the Japanese government planned to take the huge government pension fund, worth 1.4 trillion out of the bond and transfer it to the stock, the foreign media commented: “The Japanese government pension fund has given the Japanese people an alarm: It is best that Abe’s economic policy will work, or your pension will be over.”

On July 29, 2016, the Japanese Government Pension Fund Management Agency (GPIF) announced the 2015 fiscal year pension fund management report, showing a loss of 5.3 trillion Yen (about 51.2 billion US dollars), a loss rate of 3.8%. Since the financial crisis, this was the biggest deficit.

Although at that time some people in Japan began to laugh at failure of Abe’s strategy, the pension loss reached 100 billion US dollars (consistent with the market entry point). However, as of today, the point of entry into the market was 17,000 points, and now the Nikkei 225 is around 22,500 points. If the Japanese pension dollar changes, it basically earns more than 30%!

After operating for so long, Japan finally realized that if to see Japan as a person, the aging Japan becomes a rich old man, and he is no longer productive. You can’t keep yourself closed and play your game with your own money. Otherwise, only investing too much money into the aging industrialization of Japan’s can’t get good returns.

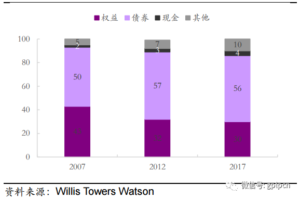

As a result, Japanese funds began to sail to the sea. As of 2017, Japanese pensions reached 3 trillion US dollars, accounting for 62.5% of GDP. 30% of the pensions was invested in overseas assets, which was incredible before 20 years for conservative Japan. As of 2017, the distribution of Japanese pension assets is as follows: the asset allocation of stocks is gradually decreasing, and assets such as real estate are gradually rising.

2014: Abe’s bottom-fishing for JP stock market

Therefore, after the thorough reform of the Japanese pension in 2006, it began to get out of the dependence towards government and completed its market operation. It is expected to provide protection for the decent life of junior people in Japan. The investment experience and case of Japan are also sufficient lesson for domestic investment institutions in our country.